The growth of global markets, super-charged by the ease of communication over the Internet, benefits consumers and producers but introduces new challenges for businesses and those who regulate them. Today, multinational firms have home offices in one country, manufacture in another, and assemble products in a third. They market to customers around the world and pay taxes in one of the many tax havens around the world.

Companies may be in the form of a single entity or a complex network of subsidiaries and affiliates domiciled in multiple national states. Discovering who is who, who owns who, and who owns what is almost impossible, time-consuming, and expensive.

The Global ELI System

The benefits of a global economy – broader markets, different products, low prices – often obscure the increased risks of dependency between the participants. As a consequence, government officials and economists failed to anticipate how a financial crisis in one country could quickly explode into a financial inferno around the world in 2007-2009.

The failure of Wall Street’s Lehman Brothers and its subsequent impact on the value of enormous securitized mortgages held by international banks and financial institutions roiled financial markets, dried up global liquidity, and escalated fears of a chain reaction of failures.

This situation highlighted a critical challenge for businesses operating in an interconnected global economy: managing the cascading effects of financial instability across borders. Effective translation can play a key role in addressing these issues. Companies can quickly adapt to changing financial conditions by ensuring accurate and timely communication across different languages. This often involves reassessing their exposure to international markets and adjusting their risk management strategies with clear, translated information. The interdependence of global markets means that disruptions in one region can have far-reaching consequences, affecting supply chains, investment decisions, and overall economic stability. By navigating the complexities of varying regulatory environments through precise translation, businesses can develop robust contingency plans to mitigate potential risks and maintain stability.

In the aftermath, world leaders recognized extensive deficiencies in the international financial system, gaps that contributed to excessive risk-taking, and delayed regulatory response.

In 2009, the G20 established the Financial Stability Board (FSB) to monitor and make recommendations to transform and strengthen the global financial system, ideally minimizing the risk of another global recession. The Board published their proposal in 2012 for a global Legal Entity Identifier (LEI), a universal, international data standard in place of the hodgepodge identification systems maintained by individual countries.

G20 members adopted the recommendation the same year, knowing that understanding the complexity of business networks and full disclosure of the connections was necessary to regulate international trade effectively. By the end of 2019, more than 1.5 million LEIs were in place.

Perils of Foreign Transactions

“Stranger Danger,” the warning all mothers give to their children, also applies to those who transact business across national borders. The international financial market is a murky, perilous space with confusing, often conflicting, regulations, and overlapping jurisdictions. A single misstep, one lapse in due diligence, can end in financial losses, damaged reputations, and even criminal penalties.

The international financial system is a mishmash of national and international regulations, multi-layered business organizations, and conflicting political interests. The combination provides an exceptional opportunity for those who would exploit the naive, mislead partners, or evade laws. Examples of the dangers targeting the unsuspecting include

- 419 scams. Sometimes referred to as the Nigerian Prince scam, international conmen, posing as representatives of a non-existing financial institution, solicit potential victims with promises of a long lost relative’s bequest if the beneficiary will only send a small administrative fee to the bank.

- Front companies. The use of privately-held, non-operating companies to divert fees and revenues to an insider without the knowledge of business partners is common in developing countries. The fake companies are also conduits to “wash” money so that funds illegally obtained appear legitimate.

- Inflated capabilities. Business practices vary around the globe so that disclosures that are commonplace in one country may be omitted or abbreviated in another. A buyer in one nation may unknowingly depend on a faux supplier in a foreign country who is an agent, not a principal, of the seller. As a consequence, the buyer is unaware of other obligations or conditions that might affect the performance of the seller. The failure of a foreign supplier can produce a domino effect on the domestic buyer, who then cannot deliver on his promises to customers.

- Undisclosed risks. Financial and operating obligations, while initiated on a subsidiary or affiliate level, can flow upward to the parent organization. Depending on the domicile of the business, the disclosure of contingent risks may not be required. In cases where disclosures are mandated, business leaders, for personal reasons, may falsify information or refuse to divulge negative information. Their omission, in turn, can expose customers, suppliers, partners, and absentee owners to unknown financial and reputation risks.

Running Afoul of Political Sanctions

International politics often leads to bewildering relationships as each country seeks to maximize its advantage. Individual nations can be allies, competitors, or a combination of both, depending on the issue. Sanctions – prohibitions of business relationships – may be general or targeted (including specific individuals) and vary from one country to another. For example, the United States currently has thirty-two different sanctions in place, according to the Treasury Department. The United Kingdom has a more exhaustive list of individuals, organizations, and regime whom they have sanctioned. Some countries like Sweden do not have national-adopted sanctions but honor those adopted by the U.N. or E.U.

Prohibited acts with a sanctioned entity include any actions that would directly or indirectly benefit the party financially. Regulatory violations can occur inadvertently due to missing, incomplete, even false information about a foreign business partner. As a consequence, due diligence – the process of discovering the relationships and connections of potential business partners – is critical before entering into an international transaction.

Ignorance of the laws is not a defense of violation as Haverly Systems, Inc. discovered in 2019. Under sanctions imposed in 2014, the U.S. Government restricted American companies from the issuance or extension of debt or equity to Russian companies. The small, New Jersey software company paid a $75,000 fine in 2019 for selling software in 2015 to a Russian, publicly-traded oil and gas company, JSC Rosneft Oil Company. During 2019, the U.S. Treasury Department settled or was awarded almost $1.3 billion in 26 cases for violations of sanctions.

The Case for a Single Entity Identifier

The balkanization of regulations and the complexity of corporate relationships complicates business due diligence and cloud regulatory oversight, especially in the world of finance. For example, one poll of senior banking officials found that financial institutions use, on average, four different legal identifiers. The survey also found that the same identifier is often used concurrently by separate business entities and that a company frequently has more than two identifiers.

There are at least ten different identifiers and related databases in use, ranging from the International Organization for Standardization Business Identifier Code to DUNS ID. The information in the individual databases for a company is rarely identical, often incomplete, and sometimes contradictory. Frustrated analysts have questioned whether eliminating all identifier codes might be better than the current smorgasbord.

The duplication and inconsistency add to the confusion of researchers trying to complete due diligence. Costs escalate due to the need to access and reconcile multiple identifiers and databases, some of which are proprietary and based in foreign countries. Small financial organizations, legally required to perform the same due diligence under “Know Your Customer” regulations as their larger competitors, are especially burdened.

Regulators have recognized the benefits of a single universal identifier for years. However, the will to implement an LEI system was dormant until world leaders experienced the pain of a worldwide recession. Even so, the use of an LEI is voluntary except for those entities engaged in OTC derivatives and securities transactions. As more companies adopt the LEI identifier by choice or regulatory mandates, the benefits to all users will increase.

Who Needs an LEI Code?

Mandatory Users

Currently, most Western countries, including the E.U. and USA, require banks, insurance companies, brokerage firms, investment companies, credit unions, and any other entity active in the financial market to have an LEI code. In short, any legal entity – corporations, nonprofits, trusts, associations, partnerships – engaged in a financial transaction or legal contract across national borders must have the code if they wish to continue in business. Natural persons, i.e., humans with their own legal identity, are not required at this time to have an LEI.

Volunteer Users

As a practical matter, anyone or any entity that does business with a foreign company today would benefit from an LEI. The value of quickly confirming the identity of a potential international partner, supplier, or customer through the vetted LEI databases is incalculable. The savings in due diligence costs alone more than justifies the expense of LEI registration and maintenance.

How to Get an LEI Code

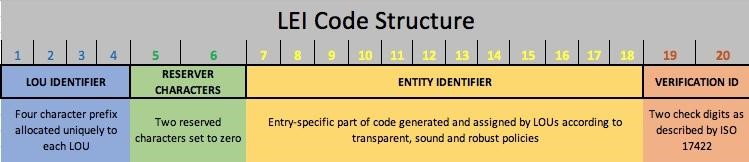

An LEI Code is a 20-digit, alphanumeric code based on the International Organization for Standardization (IOS) 17442:2019 under the authority of the international Global Legal Entity Identifier Foundation (GLEIF). Local Operating Units (LOUs) accredited by GLEIF issue LEIs, typically with the assistance of a Registration Agent like GetLEI.com, who manages and streamlines the registration process for an applicant. Following receipt and verification of the information of the Registration Form (usually about five to ten days), the LOU issues a unique LEI code to the Registrant. The current minimum registration information includes the legal name and registered address of the applicant, the country of formation, and the dates of any previous LEI assignment.

The cost of registration varies based on the choice of Registration Agent, the length of registration term, payment arrangements, and extent of bundled services offered by the Registration Agent. For example, the GETLEI Basic plan costs $69 annually and includes LEI registration, data updates and free SSL certificate.

Final Thoughts

The LEI code system is here today and its universe of users will continue to grow. While elements of the system may change over time, the basic concepts underlying its adoption will not change. The question for most businesses is not “if” they will register an LEI number, but “when.” Foresight suggests that obtaining an LEI before it might be requested by a vendor or customer, or mandated by the regulating authorities, would be wise, especially since the costs of registration are minimal. What will your business decisions?

Hi Boox Popular Magazine 2024

Hi Boox Popular Magazine 2024